This Modern Home In Miami Beach Is Perfect For A Collector And His Family

Date: 11.28.2016

Published On: Architectural Digest

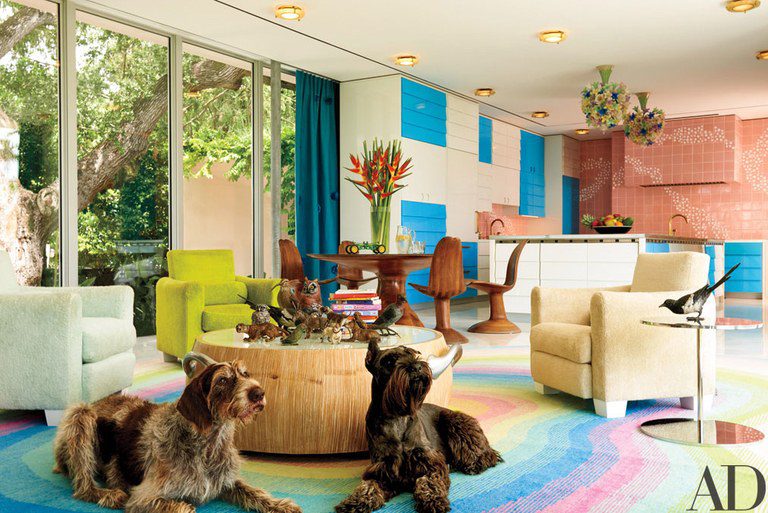

Standing in the soft glow of his perfectly pastel two-story waterfront home in Florida, George Lindemann says, “I didn’t want a white house. I have two young girls whose favorite color is pink, and because they live with two dads and two brothers, I am always looking for ways to empower them. So I made pink my favorite color, too!”

After local architect Allan T. Shulman completed the 7,000-square-foot tropical-modern home on one of Miami Beach’s Sunset Islands, Lindemann, the son of entrepreneur George Lindemann, turned to his neighbor and close friend Susan Bell Richard, who advises an impressive list of artists and designers, to zero in on the precise shade of pink. “She’s a brilliant colorist,” he explains, “and she knows the light on the island, having lived here for 30 years.” Together they spent two years reviewing exactly 74 samples of pink paint. “We painted swaths of the house with different shades and drove the boat by throughout the day to see how it looked at every hour.” The resulting hue is not unlike the sand on Harbour Island in the Bahamas.

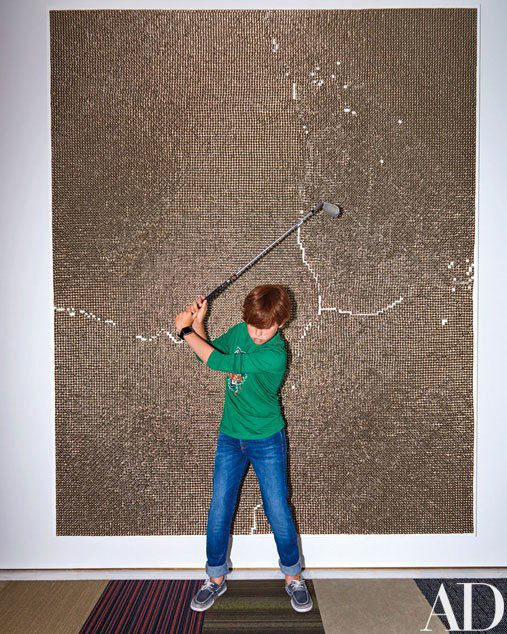

That dedication to process is also evident in the homeowner’s greatest passion, one he has been honing since he was a child: collecting. “I was seven or eight years old when I began collecting cacti, then stamps, and then, for decades, ephemera from our westward expansion,” says Lindemann, who chairs the board of the Bass art museum in Miami Beach. “But after moving to South Florida, I did what everyone else does: I started to collect contemporary.”

Now, 20 years later, the New York–born father of four lives enveloped in a trove of contemporary art and design spectacular in its scope, including dozens of abstract ceramics by Peter Voulkos and Ken Price, iconic works by Claude and François-Xavier Lalanne and Damien Hirst, and significant pieces by designers Mattia Bonetti and Ron Arad.

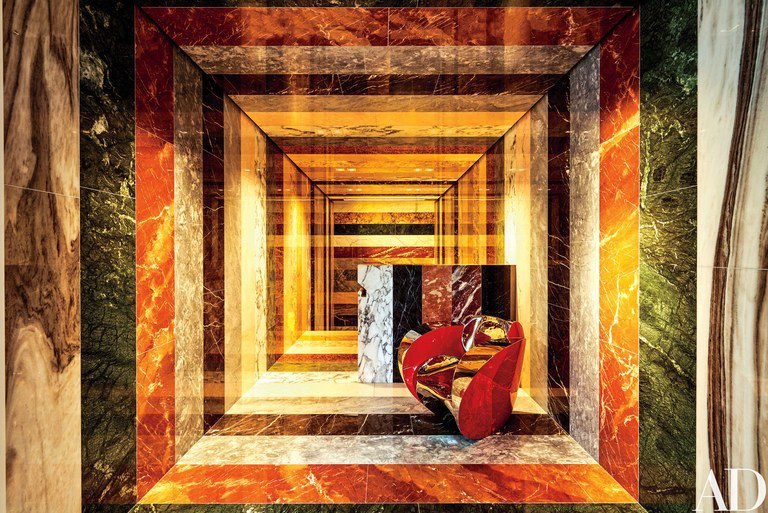

Lindemann has also commissioned a remarkable array of works, some of which were created especially for his new home—or are even, as in the case of the Martin Creed–designed staircase, integral to it. “The space was architecturally challenging,” says Lindemann of the tunnel-like stairwell, which opens to the dining room. “Nobody could figure out an elegant solution, but Martin came over and quickly saw how to take this stairway from afterthought to something really interesting.” The Turner Prize winner’s design, consisting of no less than 37 kinds of marble, is one of the most stunning features of the house.

Other commissions include a pair of side tables by Jean-Michel Othoniel, whose work Lindemann has collected for many years, and a flamboyant silver dining service by the Los Angeles–based Haas Brothers that, housed in its own four-foot-tall display case, is a sculpture unto itself. “Commissioning can be scary, because the outcome is uncertain,” says Lindemann. “But when it’s successful, like the Haas flatware, there is a lifelong attachment to the object—and to the artist—that transcends a simple acquisition.”

Not lacking for material, his interior designer, New York–based Frank de Biasi, was charged with re-packaging Lindemann’s vast collection. “The main job for me was to make sure his ideas were interpreted correctly for the long term,” De Biasi says of the three-year project. “We are both obsessed with design and art, and we continually hashed out all sorts of ideas. It’s the most fun and creative part of the process.”

Lindemann first met De Biasi 20 years ago, when the designer was working for Peter Marino, who had completed a few projects for the collector’s parents. “I liked him from the start, and when I did my first remodel in Aspen, in 2006, Frank helped me, and he has done all of my work since then. We both encourage each other to push the limits. I can’t tell you how many times I sent proposals back to the drawing board with notes like ‘not good enough’ or ‘so beige.’ I think we created our own new style,” Lindemann says with a laugh.

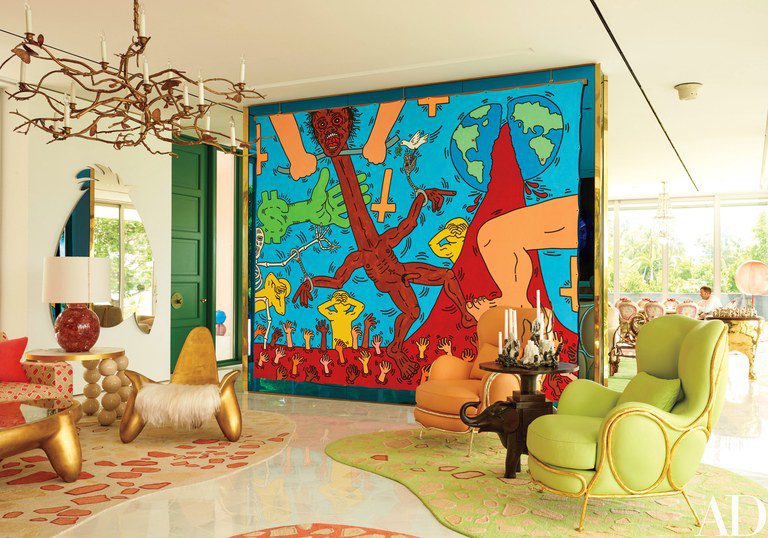

What that new style translates to is a glass-walled house that glows from within. In the living room are works by Jeff Koons, Anish Kapoor, Liza Lou, Voulkos, and Claude Lalanne, whose rambling branch chandelier hangs above a gilded cocktail table and chairs by Wendell Castle and a one-of-a-kind pair of side tables by Othoniel flanking a custom- made Jean-Michel Frank–style sofa. A very large Keith Haring painting hangs on one side of a blue- mirrored wall designed by De Biasi (“after much pleading with the team that George needed walls to hang his art on”) that bifurcates the space into distinctive sitting areas. Alex Katz’s Red House 4 hangs on the other side of the wall, overlooking the Haas Brothers service, Claude Lalanne’s crocodile chair, Do Ho Suh’s Floor Module cocktail table, and a stainless-steel side table by Martin Szekely.

“I walk around the house and see things I have owned for 30 years or longer, and they are like old friends,” says Lindemann, who has become close to a few of the artists whose work he collects. “When I moved here, Mark Handforth and Dara Friedman were some of the first people I met.” Lindemann now owns a number of pieces by the couple, including five of Friedman’s early films and several sculptures by Handforth.

Lindemann’s relationship to the art world extends beyond the confines of his home. His brother, Adam, and sister-in-law, Amalia Dayan, are art dealers, and Lindemann has been involved with the Bass since 2008. There, he helps set the general direction of the institution, which is nearing the completion of an almost $8 million renovation that includes a new wing by architects Arata Isozaki and David Gauld.

Lindemann is also bringing his interest in the environmental issues surrounding the Everglades and the East Tennessee watersheds to the museum. “Cultural institutions need to evolve with the awareness of climate change,” he says, pointing to an Ugo Rondinone outdoor sculpture the Bass recently acquired. “Its materials are water-resistant and don’t fade, which reflects our awareness of the climate issues,” he notes. “It also reflects the realities of Miami Beach. It embraces people of all shapes and color. It’s serious but lighthearted.”

The same might be said of his own pink, modern, art-filled box.